News from the Media in West Virginia, Virginia, Ohio & Maryland

November 16, 2008

W. Virginia town shrugs at poorest health ranking

By MIKE STOBBE, AP Medical Writer

HUNTINGTON, W.Va. – As a portly woman plodded ahead of him on the sidewalk, the obese mayor of America's fattest and unhealthiest city explained why health is not a big local issue.

"It doesn't come up," said David Felinton, 5-foot-9 and 233 pounds, as he walked toward City Hall one recent morning. "We've got a lot of economic challenges here in Huntington. That's usually the focus."

Huntington's economy has withered, its poverty rate is worse than the national average, and vagrants haunt a downtown riverfront park. But this city's financial woes are not nearly as bad as its health.

Nearly half the adults in Huntington's five-county metropolitan area are obese — an astounding percentage, far bigger than the national average in a country with a well-known weight problem.

Huntington leads in a half-dozen other illness measures, too, including heart disease and diabetes. It's even tops in the percentage of elderly people who have lost all their teeth (half of them have).

It's a sad situation, and a potential harbinger of what will happen to other U.S. communities, said Ken Thorpe, an Emory University health policy professor who is working with West Virginia officials on health reform legislation.

"They may be at the very top, but obesity and diabetes trends are very similar" in many other communities, particularly in the South, Thorpe said.

The Huntington area's health problems, cited in a U.S. health report, are a terrible distinction for the city, but the locals barely talk about it. Many don't even know how poorly the city ranks.

Culture and history are at least part of the problem, health officials say.

This city on the Ohio River is surrounded by Appalachia's thinly populated hills. It has long been a blue-collar, white-skinned community — overwhelmingly people of English, Irish and German ancestry.

For decades, Huntington thrived with the coal mines to its south, as barges, trucks and trains loaded with the black fuel continually chugged into and past the city. There were plenty of manufacturing jobs in the chemical industry and in glassworks, steel and locomotive parts. Nearly 90,000 people lived in the city in 1950.

The traditional diet was heavy with fried foods, salt, gravy, sauces, and fattier meats — dense with calories burnt off through manual labor. Obesity was not a worry then. Workplace injuries were.

But as the coal industry modernized and the economy changed, manufacturing jobs left. The city's population is now fewer than 50,000, and chronic diseases — many of them connected to obesity — seem much more common.

Shari Wiley is a nurse at St. Mary's Regional Heart Institute in Huntington. She runs a program that identifies heavy school children and tries to teach them better eating and exercise habits. The effort began because of an alarming trend.

"A lot of the patients we were seeing were getting heart attacks in their 30s. They were requiring open heart surgery in their 30s. And we were concerned because it used to be you wouldn't see heart patients come in until they were in their 50s," Wiley said.

The Huntington area is essentially tied with a few other metro areas for proportion of people who don't exercise (31 percent), have heart disease (22 percent) and diabetes (13 percent). The smoking rate is pretty high, too, although not the worst.

However, the region is a clear-cut leader in dental problems, with nearly half the people age 65 and older saying they have lost all their natural teeth. And no other metro area comes close to Huntington's adult obesity rate, according to the report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, based on data from 2006.

Perhaps fittingly, hospitals are now Huntington's largest employers. Another is Marshall University, home of the "Thundering Herd" football team depicted in the 2006 film "We Are Marshall" which dominates local sports conversations.

The river runs along the edge of town, but it's not a focal point. Marshall and one of the city's remaining factories sit to the east with several blocks of hotels and office buildings farther west. A new complex called Pullman Square — which includes a movie theater and a Starbucks — is trying to become a retail and dining center and illustrates a transition to a service economy.

The area's unemployment rate was about 5 percent in September, actually a bit better than the 6.1 percent national average that month. But often the jobs are not high-paying. Many workers lack health insurance, and corporate wellness programs — common at large national companies — are rare.

Poverty hovers, with the area rate at 19 percent, much higher than the national average. In the hilly coal fields to the South, people still live in houses or trailers with drooping, battered roofs. They stare hard at any stranger in a new car. In Huntington and its outskirts, many people think of exercise and healthy eating as luxuries.

The economy needs to pick up "so people can afford to get healthy," said Ronnie Adkins, 67, a retired policeman, as he sat one recent morning on the smoking porch of the Jolly Pirate Donuts shop on U.S. 60.

Doughnut shops don't help either, of course. But breakfast pastry shops aren't the most common outlets for fatty food. Pizza joints are. They are seemingly on every block in some parts of the city. The online Yellow Pages lists more pizza places (nearly 200) for the Huntington area than the entire state of West Virginia has gyms and health clubs (149).

Hot dog places also abound, with the city hosting an annual hot dog festival every summer. "I've never seen so many places that are hot dog oriented. I guess it's a cultural thing. Appalachian," said Mayor Felinton, who grew up in Maryland and moved to Huntington to attend Marshall University and stayed put.

Fast food has become a staple, with many residents convinced they can't afford to buy healthier foods, said Keri Kennedy, manager of the state health department's Office of Healthy Lifestyles.

Kennedy said she had just seen a commercial that presented "The KFC $10 Challenge." The fried-chicken chain placed a family in a grocery store and challenged them to put together a dinner for $10 or less that was comparable to KFC's seven-piece, $9.99 value meal.

"This is what we're up against," said Kennedy, noting it's an extremely persuasive ad for a low-income family that is accustomed to fried foods. "I don't know what you do to counter that."

Lack of exercise is another concern. During a warm and sunny autumn week in Huntington — the kind of weather that would bring out small armies of joggers in some cities — it was unusual to see a runner or bicyclist. The exercise that does occur is mostly confined to a local YMCA, at campus recreation facilities at Marshall, or at Ritter Park in a tony neighborhood south of downtown.

Some attribute the problem to crumbling sidewalks in the city and a lack of walkways along busy rural roads. Others blame it on lack of motivation, as well as a cultural attitude that never included exercise for health.

There's a connection between education and lack of exercise, too, said Dr. Thomas Dannals, a Huntington family physician.

"The undereducated don't know the value of it. They don't have the drive for it. There's a reason you're successful, you've got drive. The same is true for exercise," said Dannals.

Dannals has been trying to change cultural attitudes. The local newspaper has called him "an exercise evangelist" for founding the city's triathlon, marathon and other projects designed to make exercise popular and fun. He's also spearheading a riverfront exercise trail project, called the Paul Ambrose Trail for Health (PATH).

Ambrose was a Huntington physician who died in the Sept. 11, 2001, jet that crashed into the Pentagon. Just before he died, he had been working on a U.S. Surgeon General report on obesity, and was on the plane that morning to attend an adolescent obesity conference in Los Angeles.

But the PATH project, first proposed more than a year ago, has yet to win the necessary funding. The lack of support is not surprising: Dannals can't even get a company to sponsor the Huntington marathon.

Local politicians tend to be equally tepid about improving health, said Dr. Harry Tweel, director of the Cabell-Huntington Health Department.

Smoking — a common sin in West Virginia — has been hard to control, Tweel said. When the health department tried to restrict smoking in local bars and restaurants, a group of local businesses fought it all the way to the state Supreme Court. (The restrictions were upheld in 2003.) Even hospitals have fought smoking restrictions in the past, Tweel said.

Other communities have taken more ambitious steps to control the amount of fat in local restaurant food. In July, the Los Angeles City Council placed a moratorium on new fast food restaurants in an impoverished area of the city with above-average rates of obesity. In 2006, New York City became the first U.S. city to ban artificial trans fats in restaurant foods. Other cities are considering similar measures.

Forget it, Tweel said. Not in Huntington.

"You're mentioning areas (of the country) that are well beyond this local region in accepting that kind of change," said Tweel.

"People here have an attitude of 'You're not going to tell me what I can eat.' The cultural attitude is 'My parents ate that and my grandparents ate that,'" he said.

Mayor Felinton echoed Tweel. Felinton had stomach surgery last year to help him lose weight and has been walking to work about three days a week. He has shed nearly 80 pounds and became sort of a local poster boy for weight loss. But in the midst of a re-election campaign last month, he said he had no plans to plunge into a fight over fat in restaurants.

"We want as much business as we can have here," said Felinton, who lost his recent re-election bid and leaves office in January. "As many restaurants as you have, it kind of enhances the livability. Maybe not the health."

To be fair, most people in Huntington don't seem to be aware of how poorly their city looks in national health statistics.

The latest numbers came from the CDC report, released in August, but little-publicized. It was based on survey data from 2006, comparing about 150 metropolitan areas. The Huntington area includes five counties — two in West Virginia, two in Kentucky and one in Ohio.

Of the 40 Huntington-area residents interviewed for this story, many had heard something about West Virginia being one of the unhealthiest states. But only one — Tweel — knew about the latest report showing how bad Huntington compared with other metro areas.

Some doctors, on hearing the statistics, noted the Huntington area is not in such bad shape by West Virginia standards. A recent state study found that health problems are significantly worse in the more rural coal counties to the south. But those places didn't show up in the CDC report, because they were too small.

Still, Huntington is an unusually obese place, said Dr. John Walden, chairman of the family and community health department at Marshall University's medical school.

Walden is a third generation physician in the area, but he's also traveled extensively around the world. He says it's always a little jolting coming home and realizing how obese his hometown is compared to the rest of the world.

"I don't know that I've ever been in a place where I've seen so many overweight people," he said.

©2008 The Associated Press

May 27, 2007

Spring Hill Cemetery holds a lot of history on its hilltop

By Sandy Wells

He knocked on a hollow metal door on the side of an elaborate zinc tombstone. “During Prohibition, the story goes that some bootlegger hid his stock in this monument. He just turned a screw, opened the door and reached in for a bottle.”

The monument marks the Thayer family plot. “They had a foundry on the South Side about where the old Steak and Ale used to be. They were used to working with metal. All the markers on their plot are zinc.”

The ornate zinc monument (center, with angel on top) features hollow panels that storytellers say were used by a bootlegger to store booze during Prohibition. Zinc monuments, in cemetery vernacular, are known as “zinkys.”

“See that brown needle monument over there? That’s Rachel Grant Tompkins, President Ulysses Grant’s aunt. She lived in Cedar Grove. He came to Charleston to see her. He came here on a train to inaugurate the C&O Railroad.”

“Here’s John William Cabell. He died March 7, 1906. He was a fireman who got killed in a crash at the corner of Court and Virginia streets. They put a fireman’s hat on the marker. He was in a horse-drawn wagon and got hit by a streetcar.”

Hundreds of visitors will flock to Spring Hill Cemetery over Memorial Day weekend to place flowers, crosses and tiny flags on the graves of loved ones.

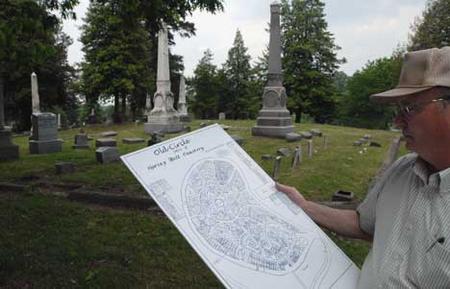

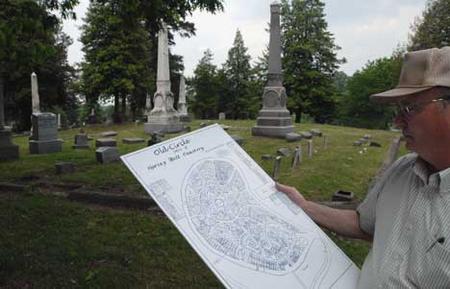

During a tour of Spring Hill Cemetery, historian Richard Andre refers to a map of the Old Circle, the oldest section. “The geometric patterns were designed by a gentleman who came here with Yankee forces in the Civil War,” he said.

The solemn duty might trigger a moment or two of reflection, then off they will go, back to the busy valley below with little thought of the history they leave behind them.

“There’s a story on every plot,” said Charleston historian Richard Andre.

Appointed chairman of the Spring Hill Cemetery Commission when it formed in 1998, Andre has collected lore about the historic hilltop graveyard since boyhood.

“I’ve been coming up here since I was 6 years old,” he said. “I came to my grandmother’s funeral in 1946. I have 13 family members buried here. This place is very familiar and dear to me. It is a sacred place.

“Whenever we talk about the cemetery now, we always use the words ‘scenic’ and ‘historic.’ It’s a fabulous 150-acre park.”

Last week, as a prelude to Memorial Day, Andre toured the cemetery with a reporter and photographer to give readers an idea of the history buried deep beneath the soil.

By next Memorial Day, the cemetery commission hopes to offer pamphlets with numbered reference maps so visitors can explore the historical labyrinth on their own, he said.

He likes to start with the oldest section, the Old Circle, where tombstone names read like a Charleston street map: Quarrier. Ruffner. Laidley. Truslow. Hale. Shrewsbury.

“Here’s Alexander W. Quarrier, a granite monument that’s over 100 years old and just as shiny as the day it was made,” he said.

A towering shaft of granite marks the grave of state Supreme Court Justice James Brown. “This is our most impressive monument,” Andre said. “It weighs about 35 tons. They needed 22 horses to pull it up Cemetery Hill.”

Sharing historical tidbits between stops, he said Spring Hill earned official city cemetery status in 1869. Graves with older dates were moved from other places. “Like Ruffner Park on the Boulevard. That was the city cemetery. We believe there are still about 100 graves down there. They just laid the markers down and buried them. The people with money had their people moved up here.”

The grave of iconic historical figure Dr. John P. Hale, a former Charleston mayor and founder of the state archives, rests under a huge flat stone called a ledger. It sits in the center of a small mound, a nod to his intense interest in the early valley mound builders.

“He was born in Franklin County, Va., in 1824 and came to Charleston as a result of falling in love with a cousin,” Andre said. “His parents nixed that and sent him away.”

A stained-glass window glows from the interior of a mausoleum that holds the remains of Mary E. Watkins, a member of a wealthy steamboat family.

The gravesite was refurbished about 15 years ago with a grant from the Kanawha Valley Foundation. Andre had marble slabs from the halls of old Charleston High School installed as steps to the mound. Each slab is engraved to represent a facet of his life: Philosopher. Mayor. Builder. Physician. Soldier. Inventor. Author. Historian.

“The guy was a renaissance man. Charleston would not be the capital of West Virginia if not for John P. Hale.”

Near the mound lay the remains of James Clark Welch. “He was with Dr. Hale’s artillery battery at the Battle of Scary Creek below St. Albans. The Yankees were bombarding each other, and Jimmy was hit by a huge piece of shrapnel. It almost decapitated him.”

He stopped at the marker for Charlie Nunnenkamp, 1886-1918. “We thought this one died in World War I, but he probably died of the flu. Whenever you see 1918, you’re either looking at a flu victim or somebody killed in the war.

“Here’s Dr. Henry Rogers and his wife, Lenora. Want your heart broken? These markers are all their dead children. 1822. 1823. 1825. 1827. 1828. They probably all died of cholera or something deadly then that we could cure in a minute now.”

He can piece together stories by carefully reading names and dates. “George Goeller was married to Molly. The child there was born July 6, 1908. Molly died July 18, 1908. If that heartbreak wasn’t enough, this son of George and Molly was born in 1905 and died in 1906. This lady had two children and neither lived beyond 2. Then she died. But her husband lived on and started another family. They’re all buried over there.”

The mausoleum in the background has a stained-glass window. It holds the remains of Mary E. Watkins.

Miles Dixson’s marker states simply that he was born in 1913 and died in 1935. Andre’s research uncovered a tragic story.

“He was a teller at the Kanawha Valley Bank. He wanted desperately to be an aviator. He went to Glen Clark’s flying school on the Kanawha River, seaplanes. When the time came to take the test, he wanted to practice. He came up here and flew over the cemetery. One of the wings came off his plane and he went down next to the mausoleum. His mother lived only three years after that.”

An epitaph forever etched into a tombstone serves as your last words, he said, “your last chance to make a commentary in this world.”

He particularly likes the one chosen by Sanford Hickel. In 1866, he patented something called “the great cold liquor quick tan.” In 1866, he patented “waterproof enamel used on leather, steel and wood.” It’s all engraved on his marker. “That’s what he wanted to be remembered by,” Andre said.

Sanford Hickel’s family had each side of his marker carved with details about inventions he patented.

Some tombstones deliver messages without a word. “Whenever you see a monument that looks like a tree, it represents someone cut down in their prime.” He rubs the carved granite bark of a large tree-shaped monument, fingers trailing along a carved leafy vine. “See how hard this granite is? And yet, look at the detail. They even put veins in the leaves. It’s probably been here 100 years. I can’t believe people could do work like that.”

A military aficionado, Andre takes special interest in the graves of Civil War veterans. “Remember the movie ‘Glory’ about the black regiment in the Civil War? Over there is John Appleton from Boston. He died in West Virginia, in Salt Sulphur Springs. He was killed by a rampaging bull. He was recruiting officers for a black battalion recruited in the New England area to go south and fight. I don’t know why he came to West Virginia. He married a West Virginian, so maybe that was it.

“Beyond that big stone over there is Thomas Lee Broun, the man who sold the horse Traveller to Gen. Robert E. Lee. Traveller was from Greenbrier County.”

Impressed with Traveller after Broun loaned him the horse, Lee said he would love to own him, Andre said. Brown offered Traveller as a gift, but Lee said he couldn’t do that. “Later, down in the Carolinas, Lee saw the horse again and Broun said he would sell him. Traveller was famous throughout the war.”

In 1993, while researching cemetery files, Andre discovered an unmarked burial plot identified in the ledgers only as Civil War soldiers. “I don’t know even if they’re Confederate or Federal,” he said. “I wrote to the VA and they sent us the stone.”

The inscription reads: HERE REST TEN OR MORE SOLDIERS KNOWN BUT TO GOD WHO DIED IN THE CIVIL WAR 1861-1865.

Andre also had street markers installed to make it easier for visitors to find their way around. Each street is named for a soldier killed in action.

Every Memorial Day, he arranges a service to honor a deceased veteran. This year’s honoree is Charles Jarvis, a 23-year-old Navy pilot killed in 1943 when his fighter plane crashed in Oakland, Calif.

Amenities have improved considerably under a cemetery-friendly city administration, Andre said. Next, the commission wants to focus on replacing and marking the trees.

A tree that probably dates back more than 50 years started growing over a monument and eventually enveloped it. “When I bring kids through here, I like to tell them the trees ate the monuments,” Richard Andre said.

“There are some remarkable tree specimens rarely seen in this area,” he said. “Many were brought up in flower pots as lot decorations by some elderly lady in a horse and buggy.”

© 2007 The Charleston Sunday Gazette-Mail

August 13, 2006

Fading feud: Hatfield relics could lose battle with nature

By Tara Tuckwiller

SARAH ANN — In a tiny hollow deep in the West Virginia coalfields, at the end of a steep, rutted dirt track, past a tangle of brush and weeds on a remote mountaintop, lies the grave of “Devil Anse” Hatfield.

On top of it, a life-size Italian marble statue of the famous feudist towers on a pedestal, 12 feet in the air. It is a jarring relic of the glory days of the Hatfield family, which rose to economic and social prominence — Devil Anse’s nephew was even elected governor — after a bloody feud with the Kentucky McCoys.

But now, there is no one to tend the graves of the legends, including dashing son Johnse, whose ill-fated romance with young Roseanna McCoy was rumored to have started the feud. (It didn’t.)

Hatfield Family Cemetery

Jean Hatfield, granddaughter-in-law of Devil Anse, has tended the cemetery for the past seven years. Her late husband, Henry, a grandson of Devil Anse, tended it for 30 years before his death, picking up sightseers’ litter and fighting back the surrounding forest that constantly threatens to reclaim the little clearing.

But now, “I’m 70 years old, and I’m a widow,” Jean Hatfield said. “I’ve had cancer twice. I live on a very limited income.”

Hatfield has a small mobile home at the base of the cemetery mountain. Out of it, she runs both a headstone business and the Hatfield Museum. Tourists stop and ask her about the feud, and she has books and family photos to sell.

“What I make on the monuments and shop is what I live on,” she said. “I can’t do the mowing and brush-cutting [at the cemetery] myself. I have to hire somebody to do it. But I can’t afford to anymore.”

‘A gem we may lose’

The Hatfield Family Cemetery is the most historically important West Virginia site from the Hatfield-McCoy feud — “maybe the most important, period,” said Bill Richardson, Logan County agent of the West Virginia University Extension Service.

"Devil Anse" Hatfield

And not just historically important. Economically important. Richardson has spent 10 years helping governments develop tourism based on the Hatfields and McCoys.

Now, the 500-mile Hatfield-McCoy trail system for dirt-bike and all-terrain-vehicle enthusiasts is one of West Virginia’s biggest tourist attractions. The Hatfield-McCoy marathon was named one of the “10 Most Enjoyable Marathons” by Runner’s World magazine this year.

But the cemetery, although listed on the National Register of Historic Places, has had no government money for upkeep.

Hatfield Museum

“Here’s an iconic piece of American history, a gem we may lose,” Richardson said.

There are no gates barring access to the cemetery. All those who want to wind their way across the mountain roads can walk among the graves.

But first, they must hike on foot up the cemetery access road, which is simply a rocky ravine washed out by stormwater that sluices down the mountain. At the top, the graves are in a clearing, once planted neatly with irises and dwarf evergreens but now usually choked by thorns and saplings. Jean Hatfield said some county government workers recently were sent to clear some brush and spray weed-killer, which has tidied things up a bit.

Hatfield Cemetery entrance

But she would like for the cemetery to be under perpetual care.

And, like Richardson, she knows the cemetery needs a new bridge and access road — not only so tourists can reach it, but also for the present-day Hatfields who still bury their dead on the mountain.

Kentucky courting tourists

On a 95-degree day during the recent heat wave, Glen Ailswick and five of his friends gathered at the base of the mountain. They had picks, shovels and Gatorade. Ailswick’s grandmother, a Hatfield, had recently died, and he was responsible for digging her grave.

“I can remember when I was a kid, looking up from the road and seeing the statute” of Devil Anse, Ailswick said, looking at what is now a wall of trees and brush. “But that was a long time ago.”

Max Brumfield, another distant Hatfield relation, spoke of decades gone by, when Logan County sheriffs were Hatfields and prison labor kept the cemetery clean.

One of those sheriffs was Tennis Hatfield, Devil Anse’s baby boy and Jean Hatfield’s father-in-law. She is full of stories about Tennis’ 12 brothers and sisters, some of whom were involved in the feud battles, some of whom she knew personally. To her, Devil Anse is simply “Grandpa.”

“I knew two of Devil Anse’s daughters and two of his sons,” she said. “I’ve sat with them when they were sick. I’ve sat with them when they died. ... Uncle Joe died in my arms.”

She is happy to share their stories with the thousands of visitors who have stopped by her information center since she opened it seven years ago. She can tell about Uncle Willis Hatfield, Devil Anse’s son, who was the last living Hatfield child until his death in 1978.

“Uncle Willis came and saw me every month, to make sure Henry was being good to me. He told him if he was ever mean to me, he’d switch the blood out of him.” She laughed.

“He was 70 years old, and my husband was 6-3 and 250 pounds, and he was saying that to him and poking him in the chest. Oh, he was a sweetheart.”

In 1975, she designed a monument — to the McCoys killed in the feud. When it was dedicated in Pike County, Ky., she and Uncle Willis and others got together with the oldest living McCoy and his family — “Uncle Jim McCoy,” she calls him — “and we had dinner together and had a big old time. We were in People magazine and everything. They said we buried the hatchet.”

In recent years, Kentucky has developed its McCoy historic sites for tourism.

“Kentucky is many steps ahead of us,” Richardson said. For example, the house where Floyd Hatfield was acquitted of stealing Old Ranel McCoy’s hog in 1878 — the incident that some people believe started the lengthy feud that left 12 people dead — has been restored.

“The Hatfield-McCoy feud has international name recognition. You can’t buy that kind of name recognition,” Richardson said. “Upgrading will bring in tourism revenue. ... But when bus tours come in here, it’s sad to say this, but if most of the sites are in Kentucky, most of the money is going to be spent in Kentucky.

“People want physical sites they can touch and interact with, and the key one for West Virginia is the Hatfield cemetery.”

© 2006 The Charleston Sunday Gazette-Mail

October 14, 2005 Mystery of the Dome

Meaning of details on panels remain unclear

By Phil Kabler

With completion of the Capitol dome restoration, details on the panels of the dome — long obscured because they were either painted or gilded to match the base — have emerged in all their golden glory.

While the project restores the dome to architect Cass Gilbert’s original specifications, it also raises a mystery: Just what do the symbols on the dome’s 16 panels signify?

“That’s a mystery to us, too,” said project contractor John Wiseman, with Wiseman Construction of Charleston.

Wiseman said he put that question to consulting architects and curators on the restoration project, and they couldn’t come up with an answer.

“They could not figure out why he chose certain symbols,” he said.

For an architect who provided copious information for every detail of his projects, state archivists have been able to find little documentation to shed light on the meaning of the symbols on the dome.

Debra Basham, state archivist, said the only item in the state collection pertaining to the panels on the dome is a 4-by-6-foot blueprint of the exterior dome by Gilbert. The blueprint details one panel of the dome, but provides no explanation other than that the raised detailing on each was to be gilded.

She said the blueprint does provide one clue to the meaning of the symbols on the dome.

The uppermost icon on each panel is an eagle, and below the eagle is a small box with the abbreviation, “SPQR.”

Basham said that almost certainly is the abbreviation of “Sentatus Populusque Romanus,” Latin for the Senate and the People of Rome — the motto of ancient Rome.

Likewise, the eagle itself was a key symbol of the Roman Empire.

Local historian Richard Andre, who conceded he has little information about the symbols on the dome, said it would be logical that Gilbert would pay tribute to the Roman Senate. He noted that many of the traditions of the Roman Senate, including the filibuster, carry on in state and federal legislative bodies today.

“Now, we’re seeing the dome as Cass Gilbert originally envisioned it, which is a striking appearance,” he said.

Wiseman, however, said the symbols on the dome are not strictly classical, and include a Medusa, an ancient Greek goddess, and draped flags with a total of 48 stars — presumably representing the states of the union at the time the Capitol was completed.

Gilbert used the dome of the Chapel of St. Louis in the Hotel National Des Invalides in Paris as the primary model for the Capitol dome.

While the restored dome now looks strikingly similar to the Invalides dome, the details on that dome are completely different.

Despite the lack of known correspondence from Gilbert regarding the panel details, Wiseman said they do know that Gilbert set aside funds from the Capitol construction budget to assure that he would have full control over the design and gilding of the dome.

“He kept $300,000 out of the original construction budget to be spent at his discretion to determine how to do these panels, and who would gild them,” Wiseman said.

In one of Gilbert’s last known letters, Wiseman said, the architect expressed his dissatisfaction with the original gilding of the dome.

© 2005 The Charleston Gazette

September 18, 2005 Port of call

Point Pleasant a favorite destination for riverboatsBy Rick Steelhammer

POINT PLEASANT — Point Pleasant may not be the state’s biggest river city, but when it comes to attracting riverboats and their passengers to spend time and money in West Virginia ports of call, it’s the best.

Located on a history-steeped chunk of land where the Kanawha River flows into the Ohio, this town of 4,600 easily tops Charleston, Huntington, Parkersburg and Wheeling as a tour stop for vessels like the Mississippi Queen, Delta Queen and River Barge Explorer. Next year, the world’s largest and newest sternwheeler, the American Queen, will add Point Pleasant as a port of call.

What’s the secret of the town’s riverboat success?

On Wednesday, an hour before the Mississippi Queen and her 332 passengers are due to arrive, it’s not hard to see.

At the new $5.8 million, mile-long Riverfront Park, where the huge sternwheeler will dock, city workers are running leaf blowers to purge sidewalks of any traces of stray debris.

Outside the park’s floodwall, a tour bus driver squeegees her motor coach’s windows to a gleaming turn. A few minutes later, a tractor rolls by, pulling the covered trolley wagon from which Mayor Jim Wilson will give commentary on the town’s points of interest while taking Mississippi Queen passengers on an informal tour of downtown Point Pleasant.

Next, a Mason County EMS ambulance parks at the mooring area of Riverfront Park’s new, 900-foot Ohio River dock to prepare for picking up a passenger who has injured her leg in a fall and requires hospital attention.

At nearby Tu-Endie-Wei State Park, a groundskeeper makes the final turns on a morning lawn-mowing circuit while re-enactors suit up in colonial era garb.

Later, a garbage truck will appear at the dock to offload the Mississippi Queen’s refuse, and a fire hose will be hooked up to replenish the floating hotel’s supply of drinking water.

“We’re a boat-friendly town,” said Denny Bellamy, Mason County Tourism Center coordinator.

“Our Riverfront Park is the nicest place to stop anywhere on the river. People can get off the boat and walk right to attractions like the River Museum, Tu-Endie-Wei Park, the downtown antique shops, historic Kincaid House and the Mothman Statue — where everyone seems to want to get their picture taken. Or they can ride tour buses to the West Virginia Farm Museum and Bob Evans Farm.

“And we’ve become kind of a truck stop for the riverboats,” Bellamy added. “Besides hauling off their garbage and filling their tanks with water, we take people from their crew into town to help them get whatever supplies they need. I think all the little things we do make a big difference.”

Being a legitimate point of historic interest doesn’t hurt, either.

In 1749, Capt. Louis Bienville de Celeron buried a lead plate at the base of an elm in present-day Tu-Endie-Wei State Park, claiming the Ohio River and the land along its tributaries to be French soil. Twenty-one years later, George Washington surveyed the area for Lord Dunmore, the colonial governor of Virginia.

In 1774, Lord Dunmore ordered a force of 1,100 Virginia militiamen to fight a like number of Shawnee warriors in the daylong Battle of Point Pleasant. The battle, a victory for the army of settlers, quelled a general Indian uprising that was taking shape on the Ohio River frontier, and prevented the British from forming an alliance with the region’s Native Americans.

Fifty militiamen and an estimated 200 Shawnees died in the battle, which some historians have argued marks the start of combat during the Revolutionary War.

More recently, Point Pleasant made international news in 1967, when the Silver Bridge connecting the town to Kanauga, Ohio, collapsed, killing 46 people.

And of course, the town is host city for the ongoing Mothman legend, which began in 1966 when five men preparing a grave in Point Pleasant spotted a man-like figure with wings taking flight from a nearby treetop. Numerous sightings continued until the Silver Bridge disaster late the following year.

“The History Channel and the Discovery Channel will both be here this week for the festival,” said Bellamy. “It looks like we’re in the Big Three now,” he said with a smile. “We’re hanging with Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster.”

As the huge profile of the Mississippi Queen approached the new Silver Bridge, more people began arriving at Riverfront Park.

Among them was Dick Smith, an intern with the Mason County Tourism Center, who couldn’t wait until the Queen came to a complete stop before pitching Point Pleasant’s tourist attractions.

Smith’s enthusiasm for his hometown was contagious. Passengers watching the docking process from upper deck railings began pumping him with questions about the Silver Bridge.

They couldn’t have found a better source. Smith moved to Point Pleasant from Buckhannon to help build the new Silver Bridge, and immediately fell in love with the town.

“I would spend hours sitting on the floodwall watching all the boats and barges going by,” he said.

Now a nontraditional student at Marshall’s Mid Ohio Valley Center, Smith is learning the tourism business by being a part of it. “I love talking to people and telling them about Point Pleasant,” he said. “This is a perfect situation for me.”

Among passengers Smith briefed on Wednesday was Gail Robbins of Monterey, Calif.

“I’ve traveled all over the world, and I’ve never found the level of hospitality greater than I’ve found it on this trip,” she said. “I love the slow, smooth way people here have of making you feel welcome.”

Robbins said she was especially interested in the region’s history, and stops at places like Point Pleasant help complete her understanding of the people, places and events that shaped the nation.

“Traveling by riverboat is the best way to see this part of the country,” she said. “If you’re driving, you spend too much time looking at the road. On the boat, you just drift by, take in the scenery and never have to worry about motion sickness.”

Charles Humphreys, director of the Mason County Tourism office, said plans are underway to complete a series of murals depicting the Battle of Point Pleasant, the Mad Anne Bailey story, Shawnee life in the area, and the Silver Bridge disaster. A sound system connected to the murals would let visitors hear the activities depicted in the art work.

“Once we get that done — we’re hoping in two years — we’ll not only get more riverboat visitors, we’ll get bus tours and school groups as well,” he said.

“This town really has ambitions,” said Dr. Sharon Yoder, a motivational speaker based in Delaware and a Mississippi Belle passenger, who stopped to chat with Mothman statue creator Bob Roach as he buffed away dull spots on the stainless steel figure’s otherwise gleaming torso.

“To meet someone as talented as Bob and to hear what the town plans to accomplish in just two years — this is great material to use in my talks. They’re leaving a legacy here.”

After the Mississippi Belle departed for Marietta, Ohio, Wheeling and Pittsburgh on Wednesday afternoon, the town only had a few days to prepare for its next riverfront arrival, the River Barge Explorer.

On Oct. 4, the Delta Queen will spend the afternoon in Point Pleasant, and return again on Oct. 31 and Nov. 5. The Explorer will return on Oct. 10, 15, 23 and 29. The excursion side-wheel paddlewheeler Chattanooga Star will give local passengers brief tours of the Ohio and Kanawha rivers starting at 7 p.m. on Sept. 28-30, and departing at 2 and 4 p.m. on Oct. 1 and 2.

“Riverfront Park was built as an economic development project, and it’s working,” said Bellamy. “When people from the boats come ashore, they want to shop and they have money to spend. It’s become quite a nice little business for the town. It helps us extend our tourism season through October and into November, and it’s only going to get bigger.” © 2005 The Charleston Gazette

July 17, 2005 Chester teapot moving to make room for B-52

By Tara Tuckwiller

The “World’s Largest Teapot” will be moved from its home in Chester, Hancock County, possibly as early as spring — but only a few yards away.

The 14-foot-tall teapot, a symbol of the pottery manufacturing region since 1938, will be replaced by a much more gigantic, antique B-52 bomber that the local Veterans of Foreign Wars post has acquired.

The nearly 50-year-old bomber will cover the equivalent of half a football field, wingtip to wingtip and nose to tail. It is 40 feet high — higher than the Great Wall of China.

“It’s going to dwarf everything in town,” said Ken Morris, mayor of the town of 2,500. He worries that the bomber is just a bit too big, but said city council has voted to support the project.

The VFW plans to build a statewide veterans memorial around the bomber, said post Commander Randy Friley, as soon as it can raise the necessary $365,000 to truck in the disassembled bomber from its current home in Oklahoma City, reassemble it, build the memorial walls and lighted walkways, purchase the necessary insurance and set aside enough for the upkeep of the loaned bomber.

And move the teapot.

“I don’t look for it until spring,” Friley said.

The teapot will move from the north side of the Jennings Randolph Bridge, which carries traffic across the Ohio River into West Virginia, to the south side, Morris said.

The teapot must be moved because the other side of the bridge is too small for the bomber, Friley said. The teapot “will actually be more visible than where it’s at right now,” he said.

The town has leased the new land for the teapot, and the VFW is paying for it, Morris said.

The teapot started life as a giant wooden barrel used to advertise Hires Root Beer, according to a written history at the local library. A Chester man, William “Babe” Devon, bought the barrel in 1938, set it up in front of his downtown pottery store, added a tin, teapot-shaped exterior complete with handle and spout, and hired teenagers to sell concessions and souvenirs out of it.

Local people kept selling things — first gifts, then lawn and garden items — out of the teapot until the 1970s, when it was finally abandoned and fell into disrepair. It would have been torn down in 1984 when C&P Telephone bought the property, except people protested. C&P donated the teapot to the town. It was moved from place to place within Chester as locals restored it. It was finally ensconced in its current location in 1990.

You can’t go inside the teapot, but a nearby convenience store sells teapot memorabilia to travelers who stop to take pictures. Morris said his T-shirt shop has made teapot shirts that “sold like hotcakes.”

The bomber idea came from local resident Pat McGeehan, an Air Force first lieutenant currently serving in Iraq, Friley said. McGeehan’s father used to fly B-52s, and was killed in a B-52 crash.

“He came to me a year ago,” Friley said, because a veterans organization must sponsor any B-52 that the military relinquishes to local control. Chester will have one of only four B-52s under municipal control nationwide, Friley said.

“It’s going to be a huge tourist attraction,” he said.

Last week, the people of Chester got a glimpse of what their new tourist attraction will look like. Another B-52, on its way from Louisiana to a Pittsburgh air show, did two flyovers of the teapot at the VFW’s request.

“A couple hundred people came just to the site,” Friley said, “and they were lined up and down the street, watching it.”

Sayre Graham, the VFW post’s senior vice commander, was one of the volunteers who restored the teapot in 1990.

“I replaced the spout, repaired the handle and put the top back on it,” Graham said. “I know the teapot.”

He said the teapot should make it through the relocation OK. “From what they tell me, they’re going to take the concrete slab and all,” he said.

Morris worries the slab will crack under the strain. But no matter what, he wants to do his part for now to keep up the teapot, as townspeople have done for two decades.

“I’ve got some paint. I was going to take a couple guys down and paint it,” he said. Some people “told me not to bother. But they’re not going to move it for a while ... I want to get it looking really nice.”

© 2005 The Charleston Gazette

July 09, 2005

Children of Chernobyl get medical help in W.Va.

Belarusian kids, battling cancer, flee radiation for the summer Katya Zabrudskaya was 7 years old the first time she left her parents in Belarus to live with strangers in West Virginia for six weeks. It was a slim shot at undoing some of the destruction that Chernobyl had wreaked on her body. Charleston doctors are involved in an international program to help children who live in the radioactive shadow of the old Chernobyl nuclear reactor. The children weren’t even born when Chernobyl exploded in 1986, but they bear the brunt of its legacy. Zabrudskaya, now 16, has hit the age limit for the program. This is her last summer break from the radiation that threatens to give her thyroid cancer. And Friday was her last visit with the doctors who help her for free. “My thyroid is enlarged because of Chernobyl,” she said matter-of-factly. Around her in the doctors’ waiting room, the other dozen or so Belarusian children joked and chattered — in their own language with each other, and in fluent English with their host moms and dads. “They’re trying to keep giving me some medicine to take back home with me,” Zabrudskaya continued. “It looks like it’s getting a little bit better. This year, I don’t have to have a biopsy.” The doctors at home try to help, she said, but they can’t really pay attention to everyone who has thyroid problems. “It’s normal there,” she said. Indeed, thyroid cancer rates among children rose up to 10 times higher in the fallout areas in the 10 years after Chernobyl, according to the Baylor University clearinghouse that compiles data from the West Virginia doctors and others. “It’s frightening,” said Dr. Steven Artz, an endocrinologist with West Virginia University Physicians of Charleston. “We biopsied two of these kids last year.” That’s two in about a dozen. By comparison, Dr. Fred Zangeneh — a pediatric endocrinologist colleague of Artz’s who also examined the children — recalls only two West Virginia children with thyroid cancer in his entire 16 years here. Chernobyl fallout is still showing up in radioactive reindeer in Norway, and radioactive sheep as far away as Scotland and Wales. But 70 percent of the radioactive fallout settled upon a corner of Belarus about the same size and population as West Virginia. That is Zabrudskaya’s, and the other children’s, homeland. At first, the Soviet government hushed up the meltdown. The world found out two days later, when Swedish scientists detected high levels of radiation wafting over from somewhere in the Soviet Union. Belarus remained under Soviet rule for several years. People weren’t evacuated. They continued to breathe radiation, absorb it through their skin, and eat it in their foods. As soon as Belarus gained its independence, families in the Charleston area — and elsewhere in the United States, and Israel, Australia and Europe — opened their homes to help children escape the radiation, if only for a brief time each summer. That was 15 years ago. “Their parents clamor to get them out of there,” said host parent Susie Marshall. This year, Marshall is hosting an orphan, the youngest boy in the group. He sat on her lap in the waiting room after his exam, laughing and talking with the other children. He will celebrate his 10th birthday next week. “He brought me two books, a mirror and a bar of chocolate” as a thank-you gift, she said. “It’s all he had.” Children often return to the same host family year after year, forging a close bond. “We call them when they’re away, at least once a month and every holiday,” said host Rachel Harper. When the children are here, “We go places like Seneca Rocks, to the movies, swimming, out to eat. Our kids always seem to love Taco Bell ... Even little things like fresh fruit. They can’t get it where they’re from. They can’t get enough of it.” The children’s homeland is wracked by disease, population decline and a depressed economy. Birth defects are up 83 percent since Chernobyl, according to a Baylor report. But medical spending per capita is less than one-tenth of that in the United States, according to the World Health Organization. One-fifth of Belarus’s farms and almost one-third of its forestland is contaminated — the region’s two significant industries. Last year, in an apparent attempt to jump-start the economy, Belarus’s government announced plans to increase agricultural production on the contaminated land. Contaminated food is a major cause of the children’s thyroid cancer, U.S. doctors have found. With little money, people find it difficult to move away from Chernobyl. “There’s not a lot of places where you can move away, actually,” Zabrudskaya explained. “Belarus, Ukraine and Russia” are all contaminated. “To move to Latvia or other places in Europe ... it’s expensive.” © 2005 The Charleston Gazette

|